TOP STORY OF THE DAY Brought to you FREE by WICU: Warrant roundup a clean sweep

All sixteen suspects alleged to be local drug dealers wanted on felony warrants during the recent roundup by local law enforcement have been located.

Clay County Sheriff Department Chief Deputy Josh Clarke confirmed Dustin Halfacre, 33, Rockville, Joseph Adkins, 43, Staunton, and Teresa Pipes, 50, Brazil, have been located and booked into the Clay County Justice Center within the past week.

Clarke provided details about the three wanted suspects taken into custody, including:

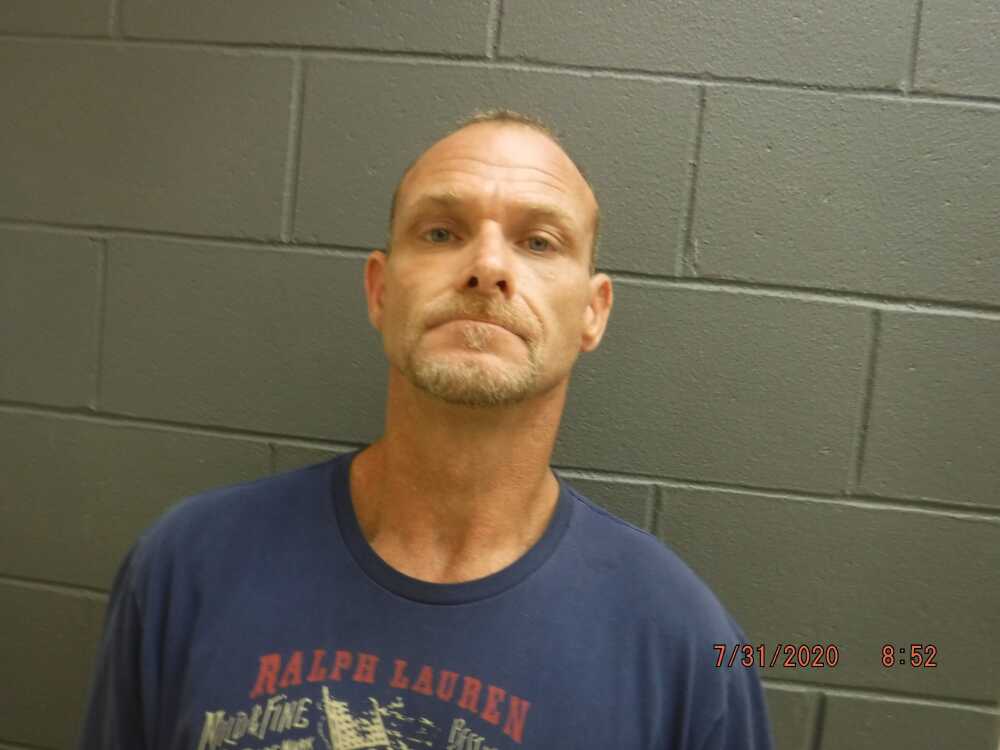

Halfacre was arrested and booked into CCJC shortly after midnight Wednesday, July 29. Halfacre faces level 6 felony warrant charges of Possession of methamphetamine, the lowest charge of the warrants filed by the Clay County Prosecutor’s Office, and two other new charges of a felony Unlawful possession of a syringe, and misdemeanor False informing. After appearing in court later that morning, Halfacre was released on his own recognizance Wednesday afternoon to await further court proceedings.

Adkins turned himself in to authorities Friday morning (July 31). He faces felony charges of Dealing in methamphetamine (F4 x2) and Possession of methamphetamine (F6 x2) on the warrant issued out of Clay Superior Court. He currently remains incarcerated while awaiting formal court proceedings.

Teresa Pipes was located and booked into jail at 11:59 p.m., Monday night. She faces felony charges of Dealing in methamphetamine (F5 x2) and Possession of methamphetamine (F6 x2) on the warrant issued out of Clay Superior Court. Pipes also has a level 6 felony charge of Escape from a warrant issued after she allegedly cut off a monitoring device on her ankle to avoid capture. Pipes remains incarcerated while awaiting formal court proceedings.

Halfacre, Adkins, and Pipes were not located during the initial 6-hour warrant sweep by officers of the CCSD, Brazil and Clay City Police departments, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and the Indiana State Police. Tactical teams of up to 10 law enforcement officers spread out over Clay County to find 16 wanted suspects on July 22.

Proactive traffic work, investigations, and community assistance leads to these types of drug warrant sweeps.

“We are always actively investigating criminal activity,” said Clark, adding its difficult to determine the number of hours it takes to create a comprehensive case file of evidence strong enough for the prosecutor’s office to obtain a warrant from the courts. “It’s proactive police work by officers that leads us to people who are up to no good. Secondly, I would say it is the community’s support and the information they provide. When you put those things together, that is how this works.”

Each case is unique, said Clarke, who explained that evidence is sometimes present, and the process can happen within a couple of days and occasionally within hours.

However, it takes time to collect enough evidence to prove a case, ranging from interviews, collecting and processing crime scene evidence, performing traffic stops, and working tips from concerned residents.

“There are many facets that have to take place during an investigation, and that can take months,” said Clarke. “Evidence is not just one piece; it takes a lot of pieces to make a solid case.”

Investigations can take up to a year or more, and a lot can happen with officers working on multiple overlapping cases, in the courts, and offenders’ lives.

“Investigators are not just working on their time. They are often working on the suspect’s time and schedule,” the chief deputy explained, adding that there have been times when a suspect subsequently quits for whatever reason. “We encourage people to quit that lifestyle, hope a person gets clean, and they quit that part of their lives and move on.”

Due to the nature of how investigations work, it is plausible that someone can “go straight” while being investigated by law enforcement.

“Fact is, that person has still committed a crime. They put themselves in that position, and there are consequences for their actions,” said Clarke, who hopes people who experience a “come to Jesus moment” understand they are responsible for their actions. “We hope they take the opportunity to do their time, get out, and live a better life. The crime doesn’t go away.”

Neither does the paperwork of the lengthy process of involved in creating each case file for a review by the prosecutor’s office and then reviewed again by the court judge.

Then comes the logistics of preparing for a roundup of multiple suspects that usually involves various agencies. The goal is to ensure everyone’s safety, which often means making sure the information about a warrant sweep operation remains private and not released to the public.

“That’s a special process, where the court seals multiple warrants to ensure officer safety,” said Clarke, who added the July 22nd warrant sweep went off without a problem. The “knock-and-announce” rule when serving an arrest warrant - derived from the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures – was enforced during the drug warrant roundup.

“Our strike teams, which were about 10 officers each, pulled up to residences where we believed they were, knocked on the doors and our suspects came out without incident,” said Clarke, who added there was no forced entry at any home on the list, and no officer performed any in-home searches. “This was a suspect round up. We didn’t have any search warrants on July 22. I don’t believe we even arrested anyone on fresh charges that day.”

Although the 6-hour warrant sweep received media attention, Clarke said it didn’t change how the small department works. Officers continued their regular routines as the jail staff and courts took over the next steps in the legal process.

It’s not the last warrant sweep the CCSD will do.

“I hope the thought process of many of the people involved in drug activity is, ‘I don’t know if they are watching’ and they stop,” said Clarke about the push to eradicate drugs from the community. “The truth is, we are continually watching, and it will catch up with you sooner or later. You never know if or when we are watching, so the best practice is not to be involved in it. We are always watching, and we could catch up with you.”