TOP STORY OF THE DAY, brought to you free by WICU: Shonna Frye, an addiction recovery success story

EDITOR'S NOTE: In the print edition containing this story, a typographical error said that Shonna had "made meth", when it should have said she "sold meth" to "make money." Our apologies.

While exact statistics are unavailable, people who become addicted to methamphetamine generally relapse far more often than they totally kick the habit.

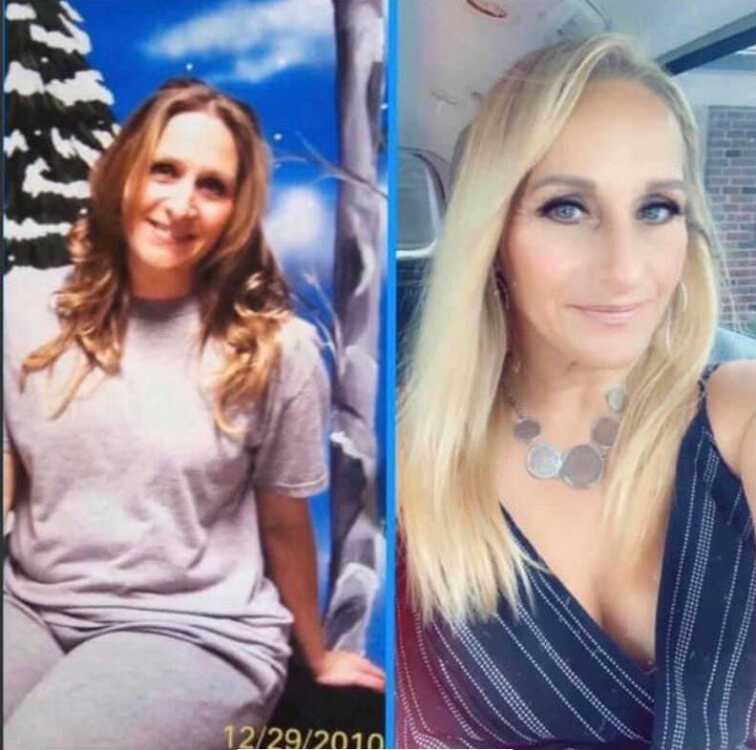

Shonna Frye of Brazil is one who proudly claims victory in the fight against meth, even though it took her going to prison to get the help she needed.

As the Brazil Times looks at drug and alcohol abuse in this edition of “Ribbon Awareness,” Frye tells her story with hopes of helping as many people as possible to avoid going through what she has.

How it started

Frye, now 50, used drugs “off and on” from the time she was 15 or 16 years old until she was 38.

“I used a little bit in school, then I quit, then I used a little bit more with my ex-husband, then I quit,” she recalls. “Then I got pregnant, and then I would use again. My heaviest use was from I was 30 until my arrest, which was when I was 38 [from 2000 to 2008].”

Frye admits falling into the trap of the “gateway drugs” such as marijuana, and that her high school boyfriend used that drug and she started there.

“We somehow got into meth, and I don’t even know how,” she said. “I did it because it was the thing to do since he was doing it, so I might as well do it.”

Frye’s parents divorced when she was 14, she recalls following another familiar pathway as a result.

“I went through a rebellious stage,” she said. “Looking back while I was incarcerated, I dealt with the whole ‘why’ thing. It was maybe to numb some of the pain I didn’t know I was experiencing. Just to kind of get away from it all. I thought it was numbing all the pain, when in actuality it was making it worse.”

She is proud of her recovery, having also been featured on a Terre Haute television station news feature. Frye considers her arrest, eventual incarceration and treatment while in prison as the main reasons for her sobriety today in addition to another personal aspect.

“I also have a very strong faith, and at the end of the day it’s God that got me through it,” she said. “It was easy to not use while I was incarcerated, even though I’m sure it was there. The real test was when I got out.

“I tell people this, and it’s so cliche, but it really is people, places and things,” Frye continued. “In the drug treatment program I went through in prison, our motto was ‘Change your thoughts, change your world’. Some of us were like ‘that’s so cheesy’, but it really is applicable now in how I think about things. Everything is a whole lot different.”

The arrest

On Dec. 11, 2008, Frye was at home when 15 federal agents came into her home at 6 a.m. and arrested her for conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine.

“I had been using meth for a long time, but earlier that year I hooked up with a gal who was originally selling it to the guy I was dating,” she said. “She eventually got me to sell for her so I was both using and selling then. At that time, I had been in a few relationships that were just bad and I had gotten to the point where I could sell meth, make money and take care of myself for once — instead of depending on the guy I was dating.

“I was also able to buy my kids things I could never afford before,” Frye continued. “I had lost custody of them years before, and although I would see them on visits they never really got the real ‘me’ because I was in my addiction.”

Frye had started selling large quantities in around February or March of 2008. That summer, someone in her “group” had gotten arrested — but the group members didn’t know about it.

As is often portrayed on TV or in movies, that person started wearing a “wire” and recording their interactions.

The group in which Frye was involved was selling very large quantities, driving to Indianapolis to pick up the drugs from Mexicans. The federal government picked up the case at that point, and started watching them undercover from June 2008 through December.

Frye obviously knew nothing about what was going on, but discovered these facts after being indicted through materials given to her lawyer.

The depth of the federal investigation was extensive, as Frye found out on the morning of her arrest when she went to the Federal Building in Indianapolis.

“They showed me a manila folder that had a bunch of pictures in it of me,” she said. “They had taken pictures of me during the six-month investigation just doing everyday things. They didn’t have any pictures of me selling drugs, because that wasn’t my charge. My charge was conspiracy, which is when one or more people conspire to commit an illegal act.

“The pictures were just to show me how much they had been watching me, and the severity of it,” Frye continued. “Here is us watching you feed your dog, or carry in your groceries. It felt invasive and intrusive.”

Frye and the person she was selling drugs had noticed some oddities during the investigation, but never were able to deduce what the government was doing.

They would notice strange cars sitting on her road for long periods of time, and another tactic not commonly known by many people.

“They opened up a car lot on my road, but no one was ever there,” she said. “We thought that was weird, but it wasn’t enough for us [to figure things out]. That’s how far we were into it. That’s what meth is — it’s the devil and it’s a liar. It makes you think you’re invincible and you’re not. You just don’t see the things you would normally see when you’re sober, and we just kept doing it.”

Frye said the investigation produced recordings of phone calls describing the conspiracy of selling, but never the specific topic of when and where the sales would take place.

Frye admits thinking as she made the numerous trips by herself to Indianapolis to conduct the transactions, and return with large quantities of drugs, that the whole thing was “just too easy.”

She never got pulled over for any traffic violations, but found later there was a specific reason for that.

“I found out later there were several occasions when police wanted to pull me over, for whatever reason, but when my name was put out on the scanner that they were told to back off because I was part of an investigation,” Frye said. “When you hear those things, you think ‘Wow’ this is a sure indicator of how serious this is.”

Facing the charges

Frye was assigned a public defender to handle her court proceedings, and felt her cooperation with the investigators kept her sentence a little lower than in some cases.

“What good would it have done for me to lie, since they pretty much had everything?” she said.

Frye faced a maximum of 10 years on the conspiracy charges. Based on her cooperation and limited criminal history, her lawyer got it down to six years (72 months, since federal sentencing is done monthly).

Frye noted that federal prisoners serve 85 percent of their sentences, and those who complete the nine-month drug program can have another year taken off their sentences.

After spending the first 19 months of her incarceration in county jails (one month each in Vigo County and Grayson County, Ky., and the rest in Clay County), she was sent to prison in Lexington, Ky., for nine months and for 18 months in Greenville, Ill.

Frye wound up serving three months short of four years (45 months) before her release on Sept. 6, 2012.

The road back

Upon her release, Frye stayed in a “halfway house” in Indianapolis for women transitioning from incarceration to re-enter society.

After two weeks, Frye was able to get a job at a Subway restaurant at the Hyatt Regency in downtown Indianapolis.

She worked six days a week, walking from her residence to work every day (roughly 16 blocks).

Once her time was over in the halfway house, Frye was able to use that experience to get a job at a Subway restaurant in Greencastle while living with her sister in nearby Fillmore.

Frye kept building upon her experiences and got a job working at a Dairy Queen being built across the street from Subway. After a month there, she was made a manager.

She then transferred to a Dairy Queen in Terre Haute.

“I’ve had a job since I got out of prison,” Frye says proudly. “Mostly restaurant work.”

Now she works at Hamilton Center in Terre Haute as a part of the “New Citizen” program, described by the facility as “supporting those who have made bad decisions that could negatively affect the rest of their lives.”

Only two individuals are chosen to participate in the program each year, one male and one female, following a set of interviews conducted by the center’s CEO and leadership team.

“They take convicted felons, because it’s hard to get good jobs, and for one year you do the program where every three months you do a rotation in different departments,” she said. “After a year, if you successfully complete the program, you get to pick the department you feel where you fit in the best. You are then offered a full-time job in that department.”

Frye began the New Citizen program in July, starting in the in-patient unit.

“That was really interesting, because I was able to see people who are going through what I went through,” Frye said. “Now, my three-month rotation is in IT [information technology]. I still go for an hour a day as part of my rotation from 7-8 a.m., and then I go to IT and work there until 3:30. I don’t get to be with the patients as much as I did before.

“IT is interesting, and I’m learning a lot of computer ‘stuff’ that I’m not familiar with,” she added. “It’s interesting, and there are a lot of jobs in that field. I’m told if I choose to stay in that department that I will learn quite a bit and it could be very profitable.”

She does not yet know the location of her final two three-month rotations, but she hopes she will like them as much as the first two.

“So far, there have been two male candidates and two female candidates [all convicted felons] who have completed the program and have really good full-time jobs there,” said Frye said, who is hoping to join that list in 2021.

Feeling blessed

Frye recognizes how fortunate she is to be in the position she’s in, considering the high rate recidivism of drug offenders.

“I know with Hamilton Center doing this that the CEO [Mel Burks] has tried to get other companies around Terre Haute to offer up the same program or something similar,” she said. “They are aware of how hard it is for felons to get jobs. I’m sure it’s a higher percentage of unsuccessful felons than successful.”

Frye understands the reality of the situation, that many places don’t want to hire convicted felons who they have to worry about whether they will go back to prison or fall back into addiction again.

“I am blessed that the girl who nominated me to do this program works at Hamilton Center, and is one of the people on my case,” she said.

One of the activities Frye enjoyed was a fashion show called “Recovery is Beautiful” sponsored at The Landing in Terre Haute by the Recovery Alliance. A local business sponsored Frye — providing her clothes to walk on a runway like fashion models do.

“That was really neat,” she said.

Lot of trust

It would seem logical and understandable if Hamilton Center were to subject people in the New Citizen program to frequent drug tests to make sure they were staying clean.

In Frye’s case, her work performance must be enough of a confirmation that she has kicked drugs for good.

“I haven’t been drug tested once,” she said. “It’s so weird. You would think they would, but they haven’t.”

Should that day come, Frye isn’t worried.

“They can do it any day of the week, and I’d pass it,” she said proudly. “I’ve even asked why, and they must believe I’m not using. I thought that was kind of interesting.”

Not looking backward

Some people in Frye’s situation claim their lives are better today for having gone through all of the self-inflicted traumas she has faced.

“I look at it like God has a plan for me, and apparently this is a part of it,” she said. “It really doesn’t do me any good to think ‘could have, should have, would have’. It is what it is, and I’m where I’m at now. Obviously He had some sort of plan for me and this is it.

“I’m 100 percent a better person than before I went to prison, and I’m grateful for that,” she said. “I’m open about telling my story to people, either in person or on social media. I feel addiction does not discriminate. There are people out there who have family members, friends and colleagues who are in addictions right now that others don’t know hear about.”

Frye said the only difference between her and some of those people is that she got caught.

“For that, I’m grateful,” she said. “I’m grateful that I got arrested federally, as opposed to state charges. If that had been the case, I would have just gone to jail for a little while, got out and went right back to doing it again.”

Frye acknowledges that lower-level correctional facilities such as jails need to have better treatment programs, but they’re not for everybody.

“You have to want to do it,” she said. “People who are stuck in their addictions have to wake up and say they don’t want to do this any more or live this life.”